U of T’s Student Legal Aid Society

The early years

Nexus/Spring 2022

Nexus/Spring 2022

by Nina Haikara

Described by Dean Emeritus (1972-1979) Martin Friedland (LLB 1958) as “a dedicated group that help improve the law school on a number of fronts,” the Student Legal Aid Society* (SLAS) was a student-led initiative that ignited a clinical education program at the University of Toronto Faculty of Law.

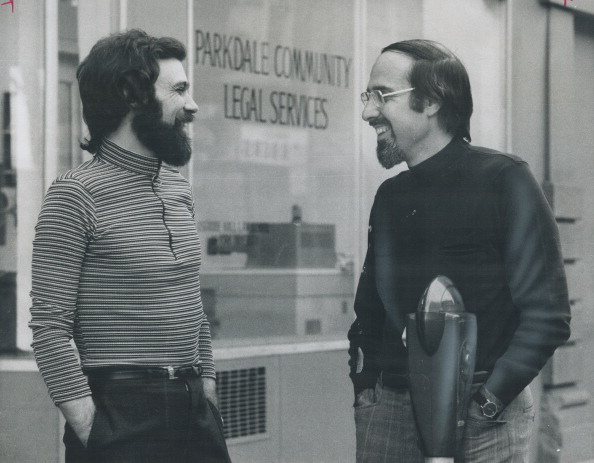

Stephen Grant (LLB 1973) recalls he and J. Robert S. Prichard (LLB 1975), were among the first cohorts to helm the SLAS executive. Prichard recalls Barb Jackman, Ellen Murray, Leslie Yaeger, Phil Zylberberg and David Downey were key leaders in growing SLAS in its early days.

“There was a general notion that we can make things better,” says Grant. “This was the end of the 1960s – peace, goodwill – trying to make the world a better place. A lot of people went to law school with the idea of changing the world from within.”

Prichard, U of T President Emeritus and Faculty of Law Dean Emeritus adds that while it was fun and meaningful work, the SLAS has come a long way, and is far more established as Downtown Legal Services.

“[SLAS] was in sharp contrast to the Parkdale clinic at Osgoode, which was a major facility and fully integrated into the curriculum with students spending a full term there for credit,” says Prichard, who is now Chair of Torys LLP and Chair of the Hospital for Sick Children.

Madam Justice Ellen Murray (LLB 1975), now retired from the Ontario Court of Justice bench, remembers there was a lot of energy and debate about whether the SLAS ought to have one central campus location or many satellite clinics. Prichard recalls a couple of rooms on the second floor of 44 St. George Street and a single room in Falconer Hall as the student administrative offices.

“We did end up having quite a few satellite clinics,” says Murray, who before her call to the Ontario bench was a sole practitioner of family and child protection before joining a family law partnership. “We had students assisting people at the Spanish Centre and I worked at a feminist centre called Women's Place.”

Grant remembers the St. George office as well as satellite clinics out of different community locations, including Regent Park and the Addiction Research Foundation (now part of the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH)).

“We were helping people who were charged with minor drug offenses, like possession of marijuana, or landlord and tenant disputes,” says Grant. “We weren't really permitted by the Law Society or anybody else to do anything of a lawyering nature that couldn't be done by a paralegal or agent. So, we had to be careful of what we took on.”

Justice Murray adds that many lawyers helped provide mentorship or advice, or sometimes offered to work with SLAS on cases they thought the students ought to know or would find interesting.

“I was involved in helping prepare a brief for a woman who had been cut-off what would now be called ODSP [Ontario Disability Support Program]. There was a lawyer who was appealing the denial by the administrative body, so I got to work on that. But it was very much case by case. If students thought they needed additional help, they might find someone to mentor them.”

Grant says most people heard the SLAS’s services by hearing from others.

“Of course, we didn't have we didn't have social media. We barely had telephones,

“Without course credit, it was just something you did because you believed in doing it,” he says. “There was clearly a need for that kind of service for people who couldn't afford lawyers and who had minor legal problems. We had to help interpret and work-out a strategy to help them through whatever difficulty they were having.”

Grant says his family upbringing and involvement in student politics at the time informed his desire to do something good with his law degree.

“SLAS did influence me and my desire to do labour law, which I did for a number of years at a union-side labour firm,” says Grant who became a leading family lawyer, specializing in complex financial cases and estate matters. He was awarded the Law Society Medal in 2006, the Advocates’ Society Medal in 2017, and the 2017 Ontario Bar Association Award for Excellence in Family Law.

Barbara Jackman (LLB 1976), one of Canada’s eminent refugee and immigration lawyers, says that while the SLAS volunteers were learning a lot, they were also spending a lot of time on their cases. She was among the students who petitioned Dean Friedland for course credit.

“It was funny, because if someone did something, they became the expert for everybody else. I did immigration, sponsorship, and helped process adoption papers – so I was the resident expert on adoption,” says Jackman.

“We were teaching each other, early-on. We were learning, but we weren't getting a credit for it, and we wanted to be able to spend more time at the clinics without sacrificing our courses.”

Jackman says when U of T Law agreed to set up a program, it needed a supervising lawyer. U of T Law alumnus Richard “Dick” Gathercole (LLB 1965) was hired.

“It was the best decision the dean made. Dick Gathercole was the kind of person who was focused, in an administrative sense. He was open, progressive and available to students.”

Among the early cases Jackman worked on was supporting a group from Women Working with Immigrant Women, an offshoot of the Spanish Centre, where there was a satellite clinic.

“As a team of students, we took on an employer in an employment standards case for treating immigrant women as subcontractors instead of employees – and we won. If you worked out the average as subcontractors they were being paid hourly, $2 or $3 an hour.”

Like Grant and Murray, Jackman says it was exciting as students to be doing work that helped members of the community.

“It also got us over of the intimidation of becoming a lawyer. As students, if you put work into it, you figured out how to do these things. And, of course, we were figuring it out ourselves.

“There were maybe four lawyers in the city who did immigration at that time, mostly processing applications and if things didn’t work out, they didn’t go to court, they just went up the ladder within immigration to try and get someone higher-up to overturn the decision.”

“But as students, we didn't have those kinds of connections, and we were in law school learning law. I remember the Supreme Court decision on fairness in Nicholson [[1979] 1 SCR 311] had a huge impact on the immigration process. We got Gathercole to argue cases in court on breaches of fairness.”

She says her SLAS experience completely influenced her decision to practice refugee and immigration law.

“I went into law school thinking because I had been involved in the student movement, I would be a labour lawyer. Getting into law school I realized organized labour was doing fine. Immigrants had no representation,” says Jackman. In 2019, she was appointed to the Order of Canada for her work as a “stalwart champion of immigration and refugee rights” who has “brought several precedent-setting Charter cases before the Supreme Court of Canada”.

"It wasn't just me who went into immigration refugee law. A lot of the people went through this program stayed within ‘people law.’”

Jackman adds community legal aid clinics are important because they are the training ground for future human rights civil liberties lawyers.

“Working in those clinics can change your approach to your whole career, in terms of what you think is important to be doing as a lawyer.

“I also think they're important in the development of skills under supervision. It's better than an articling experience in the sense that you can't do anything without going through it with the lawyer on staff. You really are under supervision, on an ongoing basis, and it's collegial. It’s a very good development experience for lawyers.” I see today’s Downtown Legal Services as part of the curriculum – part of what a law school should be. I'm glad that it’s still going. It’s a very worthwhile program.”

Justice Murray echoes the pride of being involved in something small that grew to become a much bigger part of the U of T Law school experience.

“I knew Downtown Legal Services had expanded but I didn’t know just to what extent. I'm very proud that we were involved at the beginning.”

Prichard says he looks back with great fondness on his time with SLAS.

“The people involved in SLAS were great. They were very important to me while at law school and so many have gone on to distinguished careers pursuing progressive causes. I remain very proud of my association with all of them.”

Acknowledgements: Former Student Law Society (SLS) presidents Vic Alboini (LLB 1972) and Yeti Agnew (JD 1973); the late Ken Chomut; David Downey; Leslie Yaeger; Phil Zylberberg (LLB 1974); and Frederick H. Zemans (LLB 1964), a professor at Osgoode Hall Law School Professor and founding director of Parkdale Community Legal Services.

This article has been updated to reflect that supervising lawyer Richard "Dick" Gathercole (LLB 1965) is also an alumnus of the Faculty of Law. We sincerely regret this error and thank Gathercole's classmate for notifying us.

***

*The clinical program was name Downtown Legal Services (DLS) in 1982. In the decade before, the U of T clinic was also known as the Toronto Community Legal Assistance Service (TCLA). Read more in the Spring/Summer issue of Nexus celebrating the 40th anniversary of DLS (PDF).

***

Nina Haikara is a writer and communications strategist with the Faculty of Law.